Private credit in the MENA region is now 13 years old. From a modest start in 2009, this niche financing market has mushroomed into a regional asset class with current Assets under Management (“AuM”) estimated to be over US $1 billion. These AuM comprise of four funds under two regional managers as well as several one-off transactions which have been directly completed by various investment firms and/or privately placed or syndicated to other regional or international investors. Private credit investing in the MENA region has shown increasing momentum during the past several years, with various international fund managers completing transactions in the region as part of seeking attractive investment opportunities globally. Today, discussions around private credit financings are far less about explaining to potential borrowers ‘what is private credit / private debt’ as used to be the case since market participants tend to be more knowledgeable about the product. This enhanced market knowledge means that the community of potential borrowers and advisors are better able to discern private credit’s benefits, determine which situations and corporate objectives are better served with the use of private credit versus other financing sources, and therefore focus more on how it might be utilized in their situation. Such a trend should prove to be a significant positive for the private credit market looking forward and is broadly a replica of the developments that led to the growth of private credit in the more developed markets.

Private credit – a short history

Prior to 2008, private credit was not considered a core asset class globally. The global financial crisis was a major turning point for the industry, with traditional lending shrinking as banks were forced to repair their balance sheets and comply with more stringent capital regulations (e.g., Basel) and extensive quantitative easing by central banks worldwide led to low-interest rates and flatter yield curves. As businesses needed fresh capital to refinance their existing loans (the much talked about ‘maturity wall’ in the developed markets during those times) and raise new capital to fund growth, institutional investors (through private credit fund managers) were able to fill the financing gap, attracted by private credit’s two key merits of attractive risk-adjusted returns and low correlation with other asset classes.

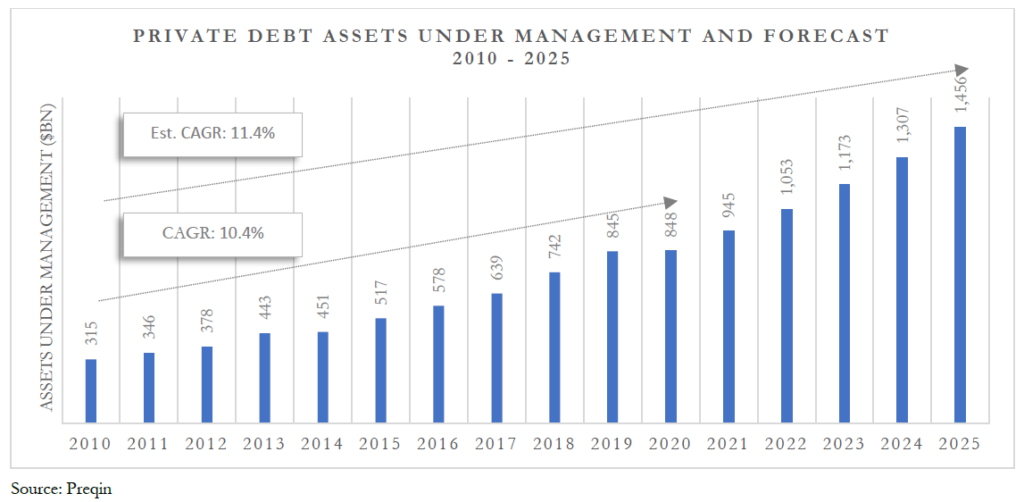

According to Preqin data and as shown in the chart below, the private credit industry reached global AuM of approximately US $848 billion at the end of 2020 and is expected to continue its growth to reach an expected c. US $1.5 trillion of AuM by 2025(1). This represents a historical 10-year CAGR of 10.4% and an estimated CAGR of 11.4% between 2010 – 2025, equivalent to a 4.5 times growth of AuM during this 15-year period. Based on Preqin estimates, private credit is well on its way to becoming the 2nd largest private markets asset class during the current decade.

(1) Preqin Future of Alternatives by 2025: Asset Classes – Data Pack

The private credit space outside North America and Europe is smaller and has represented an average of c. 7% of funds raised annually between 2006-2020 (according to Pitchbook data)(2). IFC and Global Private Capital Association estimate that annual private credit fundraising in emerging markets more than tripled from $2.4 billion in 2009 to $9.4 billion in 2018 (3). This growth is driven by various factors, among which are:

- Increasing Basel III compliance of banks, which has led to some retrenchment from middle market lending activities;

- A premium risk versus return profile offered by emerging markets private credit, particularly vis-à-vis heightened competition and deteriorating protections for alternative lenders in the U.S. and Europe;

- Low correlation of private credit with traditional asset classes, such as public fixed income and equities, has added diversification protection to investor portfolios; and

- Historically low USD interest rates, flatter yield curves and quantitative easing practices employed by central banks during the last two global crises (global financial crisis, COVID-19) significantly compressed returns on most publicly traded fixed income securities.

(2)PitchBook 2020 Annual Global Private Debt Report

(3)EMPEA “Private Credit Solutions: A Closer Look at the Opportunity in Emerging Markets”

How is private credit used in the MENA region?

Unlike the developed markets of North America and Europe, the MENA region does not have the significant private equity dry powder that will ultimately get deployed by private equity sponsors in majority-owned leveraged buyout (LBO) deals. LBOs present a significant amount of steady, recurring deal flow for private credit providers in such markets. As a result of this opportunity, and the consequent related increase in the amount of advisory intermediation and higher competition created among capital providers, private credit investing has now become highly commoditised, with deals carrying much higher leverage ratios, lower returns per turn of leverage and far more limited covenant protection as compared to the MENA region.

It is therefore important to consider what kind of situations private credit gets used in within the MENA region (if it is not driven by developed market style LBOs) and what kind of companies are ideally placed to benefit from this financing alternative.

The companies that are most likely to benefit from private credit can be broadly defined as mid-market companies. These are the subset of small and medium enterprises, or SMEs, with EBITDA of c. US $5 million – US $25 million. In the MENA region, such companies can be anywhere from 5 – 25 years old, have often been through multiple markets and industry cycles, and do not have any ‘proof of concept’ type risk. By virtue of their size, they typically will not have any access to the publicly listed or privately placed bond markets (which tend to work best in certain minimum issuance sizes that are often substantially greater than the capital requirements of such companies). Therefore, the financing options for these mid-market companies are limited to traditional bank finance, private credit, or private equity.

Private credit can be used in various transactions where bank financing options are not available or are otherwise limited and in situations where non-dilutive capital is considered more attractive than a private equity investment. These situations include (among others):

- Acquisition financings;

- Growth capital (funds for organic expansion, including capital expenditures);

- New money capital into restructuring situations;

- Dividend recapitalisations;

- Shareholder buybacks; and

- Balance sheet recapitalisations / bank debt refinancing (for example, (i) converting working capital loans into term debt to release working capital credit limits for growth, or (ii) doing a ‘term-out’ financing where shorter-term maturity debt is paid out and a more manageable debt maturity profile established).

Private credit versus bank financing in the MENA region

Why is the MENA region’s bank market unable to service all the capital needs of mid-market companies? Banks are a logical and necessary source of capital because of their ability to provide a wide range of products ranging from bank accounts, overdraft lines, undrawn credit lines, letters of credit, working capital lines (receivables factoring, invoice discounting, inventory financing) as well as medium-long term debt in the form of term loan facilities. Consequently, banks are likely the first port of call for any mid-market company looking to raise medium-long-term debt. Although ultimately, the banks are the largest single source of financing for such mid-market companies, their organisational set-up (centralised decision making), risk management practices (implementing customer credit limits and using internal ratings for credit decisions), the interaction process with their clients (bifurcation of risk assessment and relationship management), the regulatory umbrella they have to operate in (minimum capital requirements) and the IFRS accounting under which they have to publicly report their financial results under (impairment charges related to bad loans) quite often results in situations where banks will retreat from extending loans. In such cases, private credit providers can become a more logical provider of financing.

Banks are traditionally built to handle a large volume of lending transactions in a standardized manner with centralised risk management controls over the lending decisions and the following of rigid lending approval protocols and processes that can often be quite time-consuming. Credit risk is typically analysed on a backward-looking (historical) basis, which drives the internal risk ratings of companies. The perception of risk is also strongly influenced by the historical experiences of the individual banks in lending to certain sectors, with any recent credit losses or impairments in a sector often creating situations where the bank will shut itself away from taking any exposure to that sector, irrespective of what the underlying reasons for the credit losses or impairments were. The level of hard asset collateral, corporate guarantees, personal guarantees, post-dated cheques, and promissory notes from the key shareholders or owner/managers often play a critical role in the internal approval process as banks try and ensure that they can establish sufficient ‘leverage’ against the borrower counterparty in case of future negative credit events. Banks also require borrowers to maintain accounts with them if they benefit from any lending. This allows the banks not only to track the funds flow related to the borrower but also provides an extra lever of de jure or de facto cash collateral to the banks, available to be set off with any due claims the bank may have against a borrower. The depth of the relationship with key personnel at the borrower, especially the main shareholder(s), is also a significant influencer in the loan approval process. Lastly, as the only way for banks to manage the risk in their loan portfolios is to vary the relative exposure weights (these risks cannot be hedged away in the financial markets), the banks often end up significantly reducing their risk appetite during downturns towards both new potential borrowers and existing borrowers, which can create an element of inconsistency and uncertainty among market participants, including borrowers, especially during times of financial or economic stress.

This is in stark contrast to how private credit providers operate. They are far more analytical in nature. They fixate more on the future cash flows and the overall value of a business into which they are considering an investment, gaining conviction on such cash flows and business value through an intensive private equity style due diligence process which often utilises the services of a ‘Big 4’ accounting firm and/or specialist consulting firms to conduct some combination of financial and commercial due diligence. A private credit provider’s primary (but not the only) collateral would be a share pledge in a jurisdiction where various self-help remedies and English Law can be applied (Abu Dhabi Global Markets, DIFC, Cayman, BVI, to name a few). While banks are thinking about what their recovery will be if they must liquidate the assets over which they have collateral through an onshore UAE court process, private credit providers think about what the value of the business would be if they ever found themselves in a situation where they have to enforce on a share pledge and subsequently sell or own and manage the company to recover their investment. Private credit providers operating in a fund structure generally have a great deal of autonomy and flexibility to analyse situations on a bespoke basis and develop highly flexible and creative financing solutions. By design, such providers typically have a flat and non-bureaucratic approval process (driven by the relevant investment committee) and are far nimbler in their decision-making.

As a result, private credit providers end up being the more reliable source of capital for companies in particular situations. Consider acquisition financings for mid-market companies in the MENA region, for example. Assuming there are no sectoral or relationship aspects that may prevent further lending, banks will often base their credit decision on what they perceive to be their client’s current incremental borrowing capacity, irrespective of what the client will look like on a post-acquisition basis. Although not completely illogical, as their client is the counterparty they understand better, such an approach can result in very conservative credit analysis, leading to insufficient funding available for the acquirer. Such a problem would be further exacerbated if their client operates close to the permitted credit limits.

On the other hand, the private credit provider will spend significant time on the pro forma analysis of the combined company to evaluate its ongoing creditworthiness, often working with accounting firms and consultants to cross-check its investment thesis and financial projections. The private credit providers can also move more speedily during such a process, which would be critical when the financing process has to synchronize with the acquisition process (especially if there is advisor-driven competitive tension in the sale process). Bank credit committees also shy away from any financings that involve either a dividend recaptitalisation or a share buyback on account of the ‘money leakage’ and higher perceived riskiness. Private credit providers, who are staffed with personnel that possess the analytical skillset of assessing the value of a business post such recapitalisation, will be able to form better credit views on financings involving such recapitalisations or buybacks. Private credit providers can create especially attractive financing solutions where borrowers require a lot of flexibility given their intended use of proceeds (often related to securing growth capital) and business plan, whether it comes in the form of extended repayment terms (2 – 4 year grace periods, bullet maturities, etc.), a PIK interest component, toggles on cash interest, a more pragmatic security package and a generally more thought out and bespoke set of covenants, amongst other things. Depending on the situation, private credit can also work in a complementary manner with banks; for example, in situations where the appetite for additional lending has been exhausted within a bank (whether because of specific borrower, sectoral, or jurisdictional credit limits) and private credit can satisfy the need for additional capital through the provision of pari passu or subordinated capital.

Private credit versus private equity in the MENA region

An interesting high-yield bond proposal for a German company that I worked on back in the late 1990s is still etched in my memory as an ideal illustration of how some companies analyse the cost of capital of their funding options incorrectly. The company was a serial acquirer, and our proposal as their investment banker was to use a bridge loan and a high-yield bond market take-out as financing for a larger acquisition they were evaluating at the time. The company had in the past availed of bank financing supplemented with the issuance of its shares to the acquired company shareholders. We argued to the CFO that a high-yield bond, despite potentially costing high single digits in an annual coupon payment, would be much cheaper than issuing equity. “But my equity is free, it doesn’t cost me anything, and this bond is too expensive,” was the CFO’s reply. We knew we had to revisit Corporate Finance 101 to convince the CFO of the more compelling financing alternative!

When companies evaluate a private equity option in comparison to a private credit option, they compare an embedded cost with a transparent cost. The cost of capital to the selling shareholder of a private equity investment is driven by the IRR that accrues to the incoming private equity investor, multiplied by the dilution of the new equity ownership, as this is effectively the value which the selling shareholder has ‘given-up’ in exchange for cash upfront. That IRR number often runs well north of 20% in the MENA region. Furthermore, embedded within the challenges of consummating a private equity transaction is the requirement for both buying and selling parties to be fully aligned on valuation, shareholder rights, and the exit path – often leading well-intended dialogue into a stalemate. On the other hand, private credit providers are relatively agnostic on such matters and instead establish agreed limits within which they allow borrowers to operate independently. By comparison, the targeted IRR for private credit will typically be in the mid-teens range, comprising a debt-like return often comparable to bank financing rates and delivering a cash yield that can run from 8% – 12% (on a floating or fixed rate basis), with the remaining return coming from some combination of a contractual PIK return and/or performance linked upside participation. Private credit, therefore, represents a great, non-dilutive, and substantially cheaper capital source than private equity. This lower cost comes on top of no dilution of shareholder rights and no sharing of board or management control. For mid-market companies looking for growth capital, private credit provides a very attractive financing option for shareholders and owners/managers of businesses.

The future

Private credit will continue to be an established, bona fide source of capital for growing mid-market companies in the MENA region. It provides highly flexible capital tailored to the business plan needs and is non-dilutive and non-intrusive in nature. It is far more useful for companies, in particular, situations (especially event-driven situations) and, therefore, should be seen as capital that can supplement bank financings and private equity quite nicely. In terms of the cost of capital, private credit stacks up between the cost of bank financing (if available) and the embedded cost of private equity. In terms of flexibility, it is better than bank financing in almost all situations and private equity in a number of situations (depending on each case on the approach taken by the specific capital providers involved). Future regional growth of private credit as an asset class will benefit the mid-market companies referenced herein and contribute to the future regional GDP growth, economic diversification, and increasing the preponderance of the private sector, all of which are core themes within several regional economic vision plans.

The writer, Mirza Humayun Beg, is a Founding Partner of Ruya Partners Limited (“Ruya”), an Abu Dhabi Global Market based private credit investment firm (www.ruyapartners.com). Ruya is a portfolio investment of Abu Dhabi Catalyst Partners, or ADCP, a joint venture between Mubadala Investment Company and Alpha Wave Global (previously known as Falcon Edge Capital). Any views and opinions expressed in this article are solely the views of the writer.